|

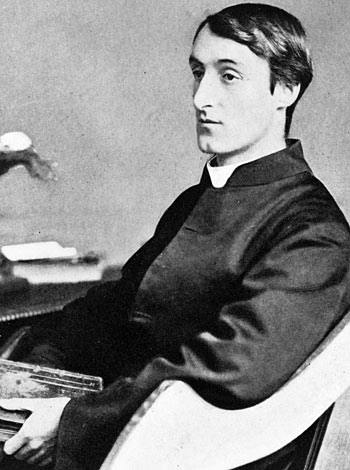

| William Blake |

Part of his enticement was

likely the nostalgia of his father who introduced him to Blake’s writing when

he was ten, but by the time he was sixteen Merton “liked Blake immensely” and

“read him with more patience and attention than any other poet.”[1] He was moved by the depth and power of

Blake’s words, especially because he could not quite figure him out.

Something about Merton was drawn

to the mystery of Blake, and I think that is carried on through his drive

towards the monastic life and Scripture in and of itself. He later acknowledged

his debt to him in The Seven Storey

Mountain, stating “through Blake I would one day come, in a round-about

way, to the only true Church, and to the One Living God, through His Son, Jesus

Christ.”[2] God utilized his appreciation for literature

– secular or Christian – to draw him nearer to Him.

His love for Blake did not cease

throughout his childhood, but rather held strong as he entered adulthood. While studying at Columbia, Merton decided to

write his thesis on Blake’s poems and fondly recalled “what a thing it was to

live in contact with the genius and the holiness of William Blake that year,

that summer, writing the thesis!”[3] Merton appreciated Blake’s deepness in

thought and verse, acknowledging his imperfections as characteristics of his

talent.

Through his studies, he came to

the revelation that Blake “had developed a moral insight that cut through all

the false distinctions of a worldly and interested morality.”[4] He consistently discovered new meanings

behind Blake’s words. In his earlier

secular journals, Merton wrote how Blake once told someone his poems were

dictated by the angels. He responds by

stating that “we have to be very careful and guard our position against

anything above that – angels, or God.”[5] Though this was before his conversion, Merton

still wrestled with such thoughts of writers he appreciated, attempting to come

to a conclusion himself.

|

| "The Poet's Dream" - William Blake |

As he did with Gerard Manley

Hopkins, Merton attempted to figure out the man behind the words. He wanted to figure out what he believed and

preached and how that was applicable to his own life. “The key to Merton’s attraction to and

treatment of William Blake lies in identifying in the life of Blake.”[6] Because Blake was drawn to Catholicism

through Dante’s writings, recognizing it as “the only religion that really

taught the love of God,”[7]

Merton recognized that truth that could be found through literature. Studying Blake’s life also allowed him to see

a change in his demeanor after conversion where he died with “great songs of

joy bursting from his heart.”[8] Such a strong desire burned within Merton as

well, who became more aware of the need for faith in his own life. Of him, Merton states, “I think my love for

William Blake had something in it of God’s grace. It is a love that has never died, and which

has entered very deeply into the development of my life.”[9] Pieces of Blake’s writing is even scattered

throughout The Seven Storey Mountain,

further exemplifying how much of an influence he had on Merton.

[1]

Merton, Seven Storey, 95.

[2]

Merton, Seven Storey, 97.

[3]

Ibid, 207.

[4]

Ibid, 222.

[5]

Thomas Merton, Secular Journal of Thomas

Merton (New York: Farrar, Straus & Cudahy, 1960), 5.

[6]

David D. Cooper, Thomas

Merton's Art of Denial: the Evolution of a Radical Humanist (Athens:

University of Georgia Press, 2008), 100.

[7]

Merton, Seven Storey, 208.

[8]

Ibid.

[9]

Ibid, 94.

.jpg)